Whether the loss of the final – e was largely responsible for throwing their lines into disorder or whether, as seems likely, the odd character of their verse results from the conscious adoption of some bizarre species of decasyllabic line, the century and a quarter of versification between 1400 and about 1525 left iambic pentameter in so strange a state that, instead of taking off from where Chaucer had left it, poets from Wyatt on had, in effect, to begin all over again.” Lydgate’s lines are often monotonously regular Hoccleve’s frequently appear to insist on stressing unlikely syllables. Wright wrote in Shakespeare’s Metrical Art: “In Hoccleve, Lydgate, and other English poets of the fifteenth century, the art of Chaucer’s iambic pentameter disintegrated. And don’t forget that hundreds of years separated them from Chaucer, almost as much as separates us from Shakespeare.

#LATIN DACTYLIC HEXAMETER SCANSION MACHINE HOW TO#

The curious thing about the Elizabethans, however, is that they couldn’t agree on how to scan Chaucer’s middle English, and so didn’t recognize it for what it was.

Anyone who has read the Faerie Queen knows just how determined. Spenser adopted Iambic Pentameter with an unremitting determination. (Though Sidney continued to experiment with accentual hexameters – for more on this, check out my post on Sidney: His Meter & His Sonnets.) The development of Iambic Pentameter began in earnest. Spenser and Sidney moved on, giving up on the idea of reproducing long and short syllables. The symbols used to scan the poem reflect Spenser’s attempt to imitate the long and short syllables of Latin. The Spenser Encyclopedia, from which I obtained the passage at right, includes the following “dazzling” example of quantitative meter in English: For this reason, perhaps, Adopting the Dactylic hexameters of Latin didn’t seem so far-fetched. They assumed that this was how Latin had always been pronounced. When the Elizabethans spoke Latin, they pronounced and accented Latin like Elizabethans. So, while we may intellectually know that syllables were spoken as long or short, we have no idea how the language was actually pronounced.

French uses the same alphabet, but how would we know how to pronounce it? Americans would pronounce it like Americans, Germans would pronounce like Germans, etc… The French accent would be gone – forever. Imagine if all memory of the French language vanished tomorrow (along with any recordings). Nobody knew what these languages really sounded like and we still don’t. Even in their own day Latin and Classical Greek were dead languages – dead for a thousand years. A circle of Elizabethan poets, including Sidney and Spenser, all tried to adapt quantitative meter to the English language. (There are no long or short syllables in English, comparable to Latin.)īut this didn’t stop Elizabethan poets from trying.

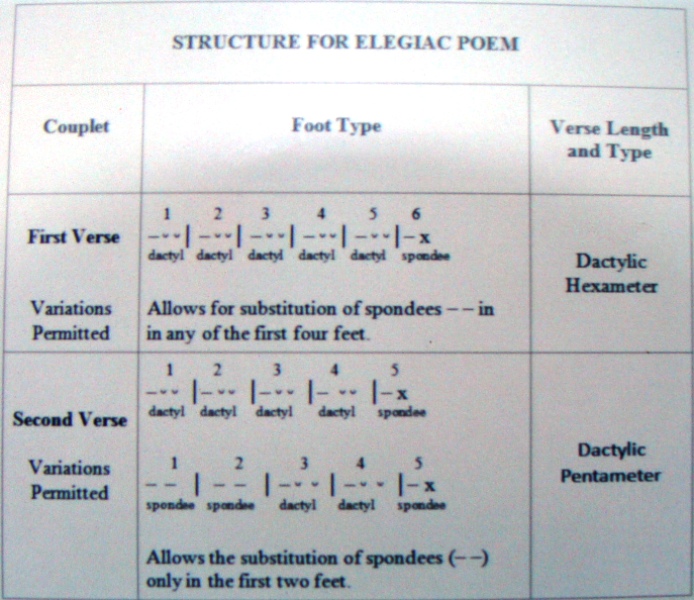

English, on the other hand, is an accentual language – meaning that words are “accented” or stressed while others are, in a relative sense, unstressed. Latin uses quantitative meter, a meter based on alternating long and short syllables. But poets couldn’t simply adopt Latin’s dactylic hexameter or dactylic pentameter lines. Since meter was a feature of all great Latin poetry, it was deemed essential that an equivalent be developed for the English Language. Iambic Pentameter originated as an attempt to develop a meter for the English language legitimizing English as an alternative and equal to Latin (as a language also capable of great poetry and literature). Latin was essentially the second language of every educated Elizabethan and many poets, even the much later Milton, wrote poetry in Latin rather than English.

Latin was still considered, by many, to be the language of true literature. MaMore typos, spruced up, note on Chaucer added.ĭuring the sixteenth century, which culminated in poets like Drayton, Sidney, Spenser, Daniel, and Shakespeare, English was seen as common and vulgar – fit for record keeping.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)